- Home

- Johannes Anyuru

They Will Drown in Their Mothers' Tears

They Will Drown in Their Mothers' Tears Read online

THEY WILL DROWN IN THEIR MOTHERS’ TEARS

THEY WILL DROWN IN THEIR MOTHERS’ TEARS

JOHANNES ANYURU

Translated from Swedish by

SASKIA VOGEL

First published as: De kommer att drunkna i sina mördrars tårar

© 2017 by Johannes Anyuru

Published by Norstedts, Sweden, in 2017

Published in agreement with Norstedts Agency

Translation © 2019 by Saskia Vogel

Two Lines Press

582 Market Street, Suite 700, San Francisco, CA 94104

www.twolinespress.com

ISBN: 978-1-931883-89-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-931883-90-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Anyuru, Johannes, 1979- author. | Vogel, Saskia, translator.

Title: They will drown in their mothers’ tears / by Johannes Anyuru ; translated by Saskia Vogel.

Other titles: De kommer att drunkna i sina mördrars tårar. English

Description: San Francisco, CA : Two Lines Press, 2019. | “Originally published as De kommer att drunkna i sina mördrars tårar”--Title page verso.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019016023 | ISBN 9781931883894 (hardcover)

Subjects: | GSAFD: Dystopias.

Classification: LCC PT9877.1.N98 D413 2019 | DDC 839.73/8--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019016023

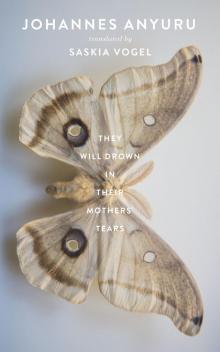

Cover design by Gabriele Wilson

Cover photo by Jasper James / Millennium Images, UK

Typeset by Sloane | Samuel

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

In the name of God, most merciful, most compassionate

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

There is no such thing as Guantanamo in the past

or Guantanamo in the future.

There is no time,

because there is still no limit to

what they can do.

PRISONER

freed after thirteen years

in Guantanamo Bay

What occurred inside the houses?

Practically nothing.

It went too rapidly to really happen.

Imagine an alarm clock on a nightstand

set to measure out the time in seconds

is caught off guard by its own liquefaction

and then boils up and whirls away as gas

and all this in a millionth of a second.

HARRY MARTINSON

Aniara, sixty-seventh song

Wind comes blowing in. It lifts up sand from the playground in front of the apartment blocks and a scattering of dried grass. The two girls on the old swings swing higher.

I watch them through the window. Their laughter doesn’t reach me, but I hear hoarse panicked screams, rattling machine gun fire, objects clattering, bodies flying.

1

This is her first memory: veils of snow whipping the hospital wings, the parking lot and poplars, the roadblocks. Before that: nothing, actually.

She shuts her eyes. Amin keeps repeating the name he’s given her. Nour. Only when hysteria creeps into his voice does she open her eyes again.

“Did you remember something new?” Face drawn, mouth tense, he’s sitting next to her in Hamad’s white Opel. The backseat is shedding foam-rubber crumbs that stick to their clothing.

She shakes her head.

In the driver’s seat, Hamad starts talking, hurrying them, and Amin wets his lips; hands trembling, he switches on the cellphone duct taped to the metal pipes on her vest. She is sitting perfectly still. Outside, stray snowflakes float past a yellow brick wall. If she were to type the four-digit code into the phone’s keypad, the metal pipes would explode, flinging out as many nails and bullets as fit in two cupped hands, and the shockwave would break bones and pulp the organs of anyone within a five, maybe ten, meter radius. Texting the code to the cellphone would have the same result.

They get out of the car. Hamad has parked on a backstreet, hidden by a dumpster. He heaves the large black gym bag out of the trunk. The cold burns her cheeks and hands, she stomps her feet to warm up.

They walk onto Kungsgatan together, but split up in the Saturday crowd. After a few steps she turns around, so Amin stops, hands in his pockets, and pretends to browse the suits in a window display.

She senses that they are interwoven.

She wishes they could have another life.

It’s February seventeenth, a little over an hour before the terrorist attack at Hondo’s comic book store.

At one point she almost steps in front of a moving streetcar—but a woman grabs her coat—the streetcar’s screech is shrill and hollow, and she ends up ankle-deep in slush, taking in the gentle snowfall in the darkening afternoon.

Again she tries to remember who she is, where she comes from, but she only gets as far as that room in the hospital, how she got up and stood by the window, leaning on her IV-stand. She remembers the swell and whine of her pulse in her temples and the cool floor beneath her feet.

She’d read that the snow on the hospital that summer night was caused by environmental devastation, or the military manipulating the weather, or it wasn’t even snow at all, but some sort of leakage from a chemical plant.

The woman who grabbed her before she stepped into the street touches her arm again and says something she doesn’t catch; the voice is dulled and distant and when she offers no response the woman walks off. Yet another streetcar passes, people go around her on the crosswalk.

At least she’s pretty sure she comes from here. Gothenburg. And that her mother is dead. Has died somehow. Was run over. No. Can’t remember. She balls her fists, opens them.

A single event can awaken the world.

She’s on the move again, back in the stream of shoppers, teenagers in puffy winter jackets, couples with strollers.

Outside the comic book store’s propped-open door, a garden candle flickers uneasily in the twilight. Behind it, a handwritten sign:

Tonight at 17:00 Göran Loberg will be signing his latest comic book and discussing the limits of free speech with Christian Hondo.

When she crosses into the light, she starts sweating, because it’s crowded and because there’s a bomb vest hidden under her winter coat.

Because of what’s coming.

She riffles through a box of comic books so as not to draw attention to herself, picks one out, flips through it.

One single act, if it’s radical enough, pure enough, can communicate with the world’s stateless masses, reestablish ties between the caliphate and the Muslims who’ve been led astray, increase the influx of new recruits, and turn the tide of the war.

Hamad’s words. Hamad’s thoughts.

She keeps flipping.

In the comic book, needle-shaped vehicles pass plantations and clouds of burning gas. Men in bulky, intricate spacesuits cross surreal desert landscapes. She’s surprised how childish the pictures are.

It actually makes her laugh, and that gives her pause.

She wonders if her body heat can detonate the pipe bombs.

One: she knows she is Muslim. Two: Swedes have killed Muslims in some sort of camp. Three: there’s this name, not hers, but it means something—Liat, someone she loved. Four: Swedes are pretending it’s peacetime, and that the death camps don’t exist. Five: she has talked it all through with Amin

, trying to figure it out.

Hamad arrives. Snow blows in through the door that’s slamming shut. He and Amin shaved off their beards the night before, and his bare cheeks makes her think of a bird skull—he looks bony and cruel. He’s wearing a black quilted jacket and a blue beanie with the logo of an American hockey team on it—a shark—which he takes off and stuffs in his pocket. By the cash register, he puts a black gym bag down at his feet.

Thirty or so people are in the store, standing around in groups or sitting on folding chairs, their outerwear balled in their arms. Christian Hondo, the shop owner, a long-haired man in a worn yellow T-shirt, turns on the microphone. Feedback wails from the two speakers that have been set out for the event.

“I suppose it’s time to say hello and welcome to you all.” The voice sounds flat and booming, doubled, as it spills from the speakers.

Göran Loberg emerges from a door behind the cash register. The audience turns around expectantly, their attention verging on devotional.

Loberg is older than Hondo, around sixty, stooped and weatherbeaten. She notices something hard about his mouth, contempt or ire. Bushy white hair, plaid shirt. He puts a notebook and pen on the table.

“We’re here to discuss your latest project,” says Hondo, “The Prophet, your collected satirical comic strips, which were published weekly online, and which contain caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed and other, shall we say…objects of blasphemy?”

Loberg nods and scratches his stubble; his entire being emanates sloppiness and a flighty disinterest in himself and his surroundings. She’s at the back of the venue. She misses some of what they’re saying. It sounds like they’re in another room, like their voices don’t match their bodies. Floating sounds.

Hondo unrolls a poster. Holds it up for the audience to see.

A group of turban-wearing, hook-nosed men are bent in prayer with cruise missiles stuck in their anuses.

It’s like she’s out of her body, watching herself like in a dream.

The bomb vest is strapped tight across her chest.

One: she can’t remember her name. Two: she doesn’t remember her real parents, whom she believes were murdered. Three: when she looks in the mirror she sees the wrong face. Four: she sometimes gets a feeling, like right now as she’s looking at this scene, that she’s been here before, here where an important event, a historic event, is being restaged.

She notices that Amin has come in and positioned himself by the front door. His face is slick with sweat even though he’s just come in from the cold. Several people in the store seem worried about the young man, miserable and marked for death, and whisper to each other. Amin glances in her direction but pretends not to recognize her.

She goes over to him.

“Amin,” she hisses. He ignores her, unsure of how to react: the plan was to spread out in the venue and wait for it to fill up. They are absolutely not supposed to be talking to each other.

“Amin. Amin.” He doesn’t even look at her. Reluctantly he lets her grab his hand. She weaves her fingers with his, squeezes. “Everything is wrong.” She’s not sure what she means by that. “Amin, everything is wrong.”

Hamad married her and Amin in his apartment a few months ago and she has been carried to this point by terrible premonitions, by her sense that she and Amin and maybe also Hamad belong together, and that she is on a mission.

“We should bail,” she hisses, and next to Amin a man in a black sweater, coat draped over his arm, gives them an irritated look. She doesn’t let it faze her. “Let’s bail,” she says, and only then does Amin allow himself to react—he tears his hand free, grabs her arm, and glares at her. Then he gives her a gentle shove, half to get rid of her and half to get her to remember the plan.

They’re supposed to spread out and wait.

Over at the table, Hondo is saying it’s not that he hates religion, but he does operate from what he calls a traditionally subversive perspective, a sentiment she doesn’t understand and can’t contextualize, “a libertine perspective,” the voice says, buzzing with treble, “a sort of trash gallery.”

She shuts her eyes. The rays of a tender headache rise to the surface then fade. One thing she hasn’t told Amin is that ever since Hamad laid out the plan, she’s been picturing the headlines. It’s like she can already remember what’s going to be written about this, afterward.

Like: Terrorist Couple Tied the Knot before the Attack. See Their Wedding Pictures Inside.

When she opens her eyes Hondo has unrolled another poster—an old woman on a bridge points a machine gun at a crowd. On the banner behind her: Refugees Welcome.

“You received a number of threats as a result of these illustrations.”

“Anyone who hasn’t suffered from death threats hasn’t said anything essential,” Loberg says, straightening his glasses. The people around her laugh. She thinks they look waxen and ghostly, like their skin is giving off a gray deathly sheen. The laughter dies out. People scratch themselves, write in notepads, lean forward, cross their arms.

She thinks: they’ll all be dead in under an hour.

It happens without warning, about twenty minutes into the discussion. Loberg is talking about how art must expand, expansion is the constituent characteristic of art, when his train of thought is interrupted by an indistinct cry that comes from a man in the crowd, he or wha…or maybe he’s screaming gun in English?

She hears the cry and thinks he’s shouting in English because he assumes Amin, who has pulled a gun from his pants in one flitting gesture, is not Swedish.

Gun. She hears the word and she hears the shot, and a woman in the front row adopts the brace position, like before a plane crash.

She is close enough to smell the gunpowder, and it’s that smell rather than the loud bang that makes her realize the attack has in fact begun.

Amin stays still, gun raised. The shot has left a smoking hole in one of the ceiling tiles above his head. She tries to catch his eye, but his gaze is fixed on some point in front of or far behind her.

People are already leaving their seats. They’re heading for the exit, feet tangling in the folding chairs, but they turn back when they see Amin. Many are pitiful and clumsy, they don’t know where to go, spinning around, knocking magazines and paperbacks off the shelves. Objects seem heavier now. Time drags then flies, the actions unfold like connected sheets. A guy with a canvas bag and a Mohawk tries to leave through the door behind the cash register but Hamad pushes him down—the sound of his head slamming against the corner of the checkout counter is awful, then he lands on the floor.

Worship God so much they think you’re crazy.

Sitting at the table, Hondo is serene. As though he thinks this is planned, part of the event—he’s even grinning self-consciously as he takes it all in. Their eyes meet.

Around them, people are stumbling and crawling over each other as though the floor itself were careening.

Hamad is shouting and his shouting finally registers with her; she realizes he’s been shouting for a while. She can’t make out the words; she can only take in the fact that he’s shouting. An irregular drawn-out sound.

A woman, face bloody, is on the floor. She grabs another woman’s sweater to try and pull herself up. Someone is hiding in a corner, behind a drift of comic books, she can see a shoe sticking out, a black winter boot—a crying man trips over it.

Hamad jumps on the checkout counter and takes a machine gun from his black gym bag; he holds it over his head like he’s showing off a spoil of war or a newborn baby, and now she can hear what he’s shouting, not words, but yo, yo, yo.

He delivers a few swift kicks to the cash register, which crashes to the floor, scattering coins and bills.

“You desecrate Islam!” Finally spitting out the words, his voice cracks in a raspy howl—the word Islam escapes as a pained moan. Fumbling, he takes another machine gun from the bag. She tears off her coat, throws it on the floor, and walks toward him. Again she feels like she’s watch

ing herself from outside her body. And that her feet aren’t really on the ground. She receives the weapon, clicks off the safety.

Hamad hands her a second machine gun, which she’s supposed to give to Amin. Her coat discarded, the sight of the bomb vest makes people cry out. They fall over themselves and each other, clearing a path for her as she walks toward Amin, who’s standing guard at the front door.

It’s Hamad who cut the pipes, filled them with nails and projectiles, and made the explosive out of household chemicals. He hung the bombs on three regular fishing vests.

She wonders if the dizziness, everything spinning around and around faster, has something to do with God.

If God is with them.

A few weeks ago, they went to the forest. They drove for over an hour into the countryside on pitted forest roads to practice shooting machine guns. It was only when she felt the weapon buck, smelled the gunpowder, and saw the spiteful flicker leave the barrel that she understood what she was about to do. That it was real. She stood there, ears ringing, the trees glowing in the headlights, pale and ghostly.

This is really happening. We’re doing it.

Amin sticks the pistol in his pants and hangs the machine gun from his shoulder. She gives him a sisterly hug. She wants to connect with the feeling that they are really doing this, doing what they had planned, but she still doesn’t really feel present. It’s more like she’s inside a memory.

One: she’s doing this out of revenge, because the Swedes killed her mother. She believes this to be true. Two: wrong, this is a mission. She’s doing this because she saw Amin on the train one rainy afternoon and knew he would lead her to her destiny, and everything that has happened since has brought her here, to Hondo’s, where she’s going to do something important, something she can’t remember.

Three: the name. Liat. She has to find Liat. Save Liat.

She rubs her temples.

There’s unrest at the checkout. Hamad jumps down and runs through the door leading to the storeroom and staff toilet. Shots ring out, loud bangs, three in quick succession. Some people in the store scream and she tries to hush them, awkwardly and embarrassed at first, then with increasing aggression:

They Will Drown in Their Mothers' Tears

They Will Drown in Their Mothers' Tears